This page is for those who have a copy of Let Your Music Soar and are following the link listed in the book for more information. But either way, you can all take a look and maybe be inspired to get a copy of the book.

This writing begins on April 8, 2019 at 8 AM and will continue with additions as I gather my thoughts.

I have added more exercises and concepts around the “One Minute Exercise” that are not already in the book. The One Minute Exercise sets up an extreme physical intensity range (which results in the dynamic range) as a support to expression. By playing a piece of music forcefully for a few seconds and then playing the same section of that piece extremely delicately for the rest of the minute, allows the mind, the body and the muscle memory to “feel” a wide intensity range. Once it is felt the player will naturally use it and that’s all there is to it. However in some cases some more guidance and explanation is necessary. And that’s the reason for the book. In my workshops I can guide the participant until they reach the place they need to be, to understand and experience full tilt expression. So I will begin to write about some needed techniques and ideas.

PRE-EXERCISE EXPERIENCE OF THE INTENSITY/DYNAMIC RANGE.

The first thing I do now in my workshops is ask everyone to touch the back of their hand with a finger from the other hand and do it in a way where they can almost feel the touch without actually making contact. What’s happening is that the finger might be just touching a hair on the back of the hand and therefore there is some other sensation before the actual contact. I explain that this is what I mean my extremely delicate. And this is the incredible effort and focus to be able to play a true pianissimo.

Then I ask the participant to jump for door key placed over the door frame. This is higher than they have ever jumped. They only have once chance to get the key. Show me how you are going to do this jump. That’s what I mean when I say forceful. It’s a true fortissimo.

Since playing music is a physical activity, establishing the dynamic range in physical terms (intensity) is extremely helpful. So I go from doing this touch and jump physical experience to then applying it to the instrument or voice, explaining that I’m not looking at the sonic experience but the purely physical experience, because it is the physical action, the physical dance of touch, motion, placement, pressure that is the controlling factor in performing music. i.e. What happens with the sound is entirely dependent upon what you do physically. And that’s where we feel the expression. i.e. we can play air-guitar, not make a sound, but feel all the expression. When we play music we get to experience the sound coming out as a direct result of the physical dance and the sound is mirroring the physical dance. Wow!

CONSIDER THE AUDIENCE

A friend communicates with me regularly about his performance experience because he’s somewhat new at this. I asked him; “What do you experience when you are playing music to an audience?” He said that he likes watching people’s reactions - he likes connecting with people in the audience - and he likes seeing when people smile back and him. He notices when people in the club are getting up or talking, or going to get a drink. I asked him; “What do you want from an audience?” He told me all he wants is for them to pay attention to what he’s doing. I asked him; “How can you expect the audience to pay attention to what you are doing whey you yourself are not paying attention to what you are doing?”

The importance of this story is that as performers, music wants our attention. We will receive all the rewards if we give it our attention. The focus on keeping the dynamic/intensity range wide by touching upon the extremes and also keeping the dynamic moving so no two notes have the same dynamic is the best way of offering that attention. The reasons for this are profound. Many of these reasons are offered in the book.

EVA CASSIDY and CHRIS BOTTI

Listen to these examples and you won’t have to do anything else. LOL!

Looking at intensity variation under a microscope can be misleading. Every swell and jump and wave can feel distracting. But that's only when we are looking so closely at the details. In the next video segment Eva Cassidy is singing the Tennessee Waltz. She uses the most extreme and abrupt intensity variation you could imagine. Yet it is absolutely musical, beautiful, expressive, and every note is sweet.

EVA CASSIDY

And in the next video listen to the Trumpet of Chris Botti as he plays to Sting’s wife and follow his intense and beautiful dynamic/intensityvariations.

CHRIS BOTTI

A NEW REVELATION 2-27-25 - A magical experience

First it is essential to contemplate the fact that music performance is not about the sound, but is an entirety physical dance that determines if, when, what sound is going to result. This is simply the reality whether you like it or not. Remembering this has immensely practical benefits for the player.

It's easiest to explain the magic by envisioning a piano keyboard where you can see/visualize everything that's happening. As I apply all the infinite physical variations of position, touch, pressure, motion, with arms, hands, fingers (all the required and controlling actions necessary for the music to happen), I will notice that there is an immediate sonic response mirroring and shadowing every subtle action no matter how delicate it is or how fast it goes by. That's the magic and the miracle.

Yes. It feels as if the music is sparkling out of the tips of my fingers. Though this is a beautiful vision it's not reality and it is a distraction to the job at hand.

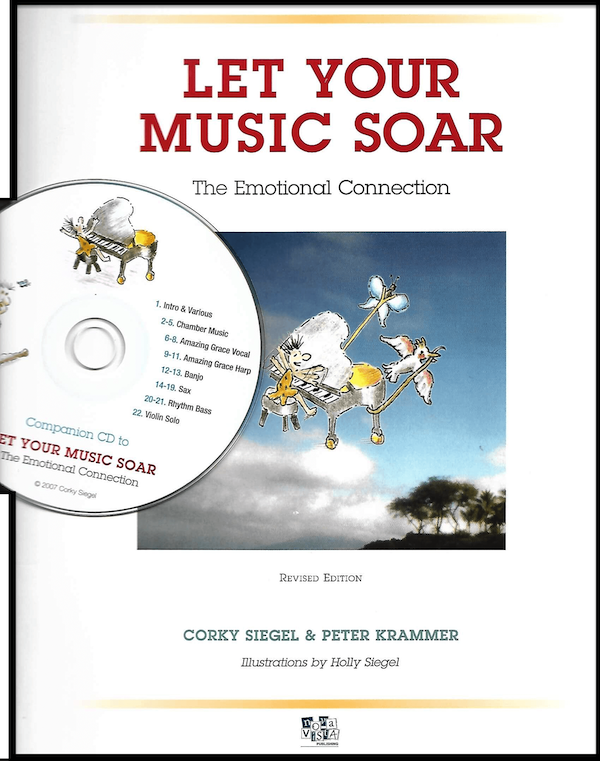

AUDIO FROM BOOK

This is in case you lost the CD that’s in the book or just want to listen from here because it’s easier.

MAKE SURE YOU HAVE THE BOOK FOR THE EXAMPLES TO MAKE SENSE

For the examples below, the musicians played a short excerpt. I gave them instructions. They played again. And this is the result in real-time. For the more radical version of dynamic use I provide links to YouTube performances above.

Also, please have your book on hand as you listen to the examples so you can understand what is going on and the purpose.

INTRO AND VARIOUS EXAMPLES: In order to experience the essential subtleties, make sure you are listening in a quiet environment or using earphones and have the volume level up so it feels like the musicians are right there in the room with you.

Tracks 2, 3, & 4: Chamber Music: Be prepared to jump around among Tracks 2, 3, and 4. Make your own comparisons between the three tracks. Study each track several times and notice how your experience deepens and changes.

Track 5: CROSS DYNAMICS - Chamber Music: Now listen to this example of Cross Dynamics. Compare this track to the other tracks, especially Track 2 (No Dynamics), and respond again to the list of qualities in the book. (Cross dynamics mean that each member plays their own dynamics even if they are opposing i.e. one is playing a crescendo and the other is playing a decrescendo.)

Track 6: AMAZING GRACE—No Dynamics: Marcella sings this beautifully, even though she was instructed to sing only what is written, with no dynamics and no ornamentation. Even without the use of dynamics, the music is beautiful—of course, it’s Marcella Detroit!! (Read about this in the book)

Track 7: AMAZING GRACE—Block Dynamics: Track 7 uses a very common style of written dynamics. (See the score in the book.) This very basic form of dynamics is called “block dynamics” because the dynamic changes take place over longer periods or “blocks” of time.

Listen to just the beginning of Track 7 as Marcy drops her dynamic level abruptly from a mf to a pp (from the full to very delicate ranges), as is written in the score and under the words “how sweet the sound.” With that drop in dynamic, you can feel a special pocket of emotion appear. (Listen to the track again.)

Then Marcy begins the crescendo under the words “that saved a wretch like me.” As the dynamic begins to increase in intensity, notice that there is a little boost of emotional energy. As the crescendo continues to grow, the emotional quality is sustained throughout the whole phrase.

Listen to the first two lines, from “Amazing Grace how sweet...” up to “...a wretch like me,” and then compare that to the same two lines on Track 6. Do you notice the differences?

Make sure you are referencing the book because there are some extensive points that are made.

Track 8: AMAZING GRACE—With the Wiggles: In Track 8, Marcy applies the wiggles, constantly varying the dynamics so no two adjacent notes have the same dynamic value. Every note is going somewhere or coming from somewhere dynamically. She did this within as wide a range as possible. The piano also adds some wiggles. The transcribed result of Marcy’s performance is in the book. Listen to Track 8.

Every note should be going somewhere or coming from somewhere dynamically.

Tracks 9, 10, and 11 - AMAZING GRACE - harmonica

Track 12 and 13 - BANJO: Composed and played by Michael Miles

In Tracks 14 through 19, Jim Gailloreto demonstrates how to establish a range and explore the wiggles. What you hear is an unrehearsed documentation of the results of this exploration.

Notice how Jim starts out “delicate” and then explores “extremely delicate.”

Notice how each of these three wiggle experiments, Tracks 17, 18, and 19, are quite different from one another. You can hear the spontaneity in these performances. You may also notice some space available for more “forceful” playing.

NOTE fROM THE BOOK: The fact is, though I prefer using extreme dynamics in my playing, they are part of a stylistic choice. Whether or not you choose to play with extreme dynamics, you should know them. If they are in your mind, in your soul, in your muscles and in every pore of your body, you will be able to call upon them when your heart is ready.

Track 20 and 21 BASS GUITAR: Bob Lizik, who is Brian Wilson’s (The Beach Boys) bass player, stopped by my studio to visit with me. I described what I was recording and had him try this experiment. Track 20 and Track 21 are examples of Bob’s spontaneous and unrehearsed application of an extreme range of dynamic flow.

Track 22 - SOLO VIOLIN is performed by Rachel Barton-Pine, an artist whose natural artistic sensitivity includes the constant flow of extreme dynamics. The work is a composition of mine called Opus 11, from the Chamber Blues Suite. - The full musical score is below.

I had my fun with the dynamics. From here on out I just let the artist do what feels right. Normally when you do this, the artists will just play mostly one dynamic range and things will go flat. So keep that in mind, especially if you are a composer.